Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

World History

Related: About this forumOn this day, July 3, 1938, LNER Class A4 4468 Mallard set the world speed record for a steam locomotive.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/July_3• 1938 – World speed record for a steam locomotive is set in England, by the Mallard, which reaches a speed of 125.88 miles per hour (202.58 km/h).

LNER Class A4 4468 Mallard

Mallard at the National Railway Museum, York

Type and origin

Power type: Steam

Designer: Nigel Gresley

Builder: LNER Doncaster Works

Serial number: 1870

Build date: 3 March 1938

Withdrawn: 25 April 1963

Restored: 1963

Disposition: On static display at the National Railway Museum, York

LNER Class A4 4468 Mallard is a 4-6-2 {"Pacific"} steam locomotive built in 1938 for operation on the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) at Doncaster Works to a design of Nigel Gresley. Its streamlined, wind tunnel tested design allowed it to haul long distance express passenger services at high speeds. On 3 July 1938, Mallard broke the world speed record for steam locomotives at 126 mph (203 km/h), which still stands today.

{snip}

1938 speed record

On 3 July 1938, Mallard claimed the world speed record for steam locomotives at 126 mph (203 km/h) during a trial run of a new, quick-acting brake, known as the Westinghouse QSA brake. The speed was achieved during the downward grade of Stoke Bank, south of Grantham at milepost 90¼, between Little Bytham and Essendine stations. Mallard hauled a seven-coach train, including a dynamometer car which housed apparatus to record the speed. The speed it recorded exceeded the previous record speed of 124.5 mph (200.4 km/h) set in Germany in 1936 by DRG Class 05 No. 002. Mallard was just four months old at the time of the record, and was operated by driver Joseph Duddington, a man renowned within the LNER for taking calculated risks, and fireman Thomas Bray. Upon arrival at London King's Cross, driver Duddington and inspector Sid Jenkins were quoted as saying that they thought a speed of 130 mph (209 km/h) would have been possible if the train did not need to slow for a set of junctions at Essendine. There was also a permanent speed restriction of 15 mph (24 km/h) just north of Grantham station, which slowed the train as they sought to build up maximum speed for the descent of Stoke Bank.

The A4 class previously had problems with the big end bearing for the middle cylinder, so the big end was fitted with a "stink bomb" of aniseed oil which would be released if the bearing overheated. After attaining the record speed, the middle big end on Mallard did overheat {and cause the locomotive to be restricted to run at} reduced speed, running at 70–75 mph (113–121 km/h) onwards to Peterborough, and was sent to Doncaster Works for repair. This had been foreseen by the publicity department, who had many pictures taken for the press, in case Mallard did not make it back to Kings Cross. The (Edwardian period) Ivatt Atlantic that replaced Mallard at Peterborough was only just in sight when the head of publicity started handing out the pictures.

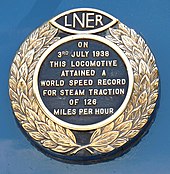

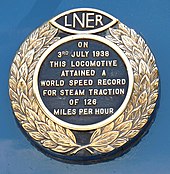

Mallard speed record plate

Mallard topped Stoke Bank at 75 mph (121 km/h) and accelerated downhill. The speeds at the end of each 1 mi (1.6 km) from the summit were recorded as: 87.5 mph (140.8 km/h), 96.5 mph (155.3 km/h), 104 mph (167 km/h), 107 mph (172 km/h), 111.5 mph (179.4 km/h), 116 mph (187 km/h) and 119 mph (192 km/h); half-mile (800 m) readings after that gave 120-3/4, 122-1/2, 123, 124-1/4 and finally 125 mph (194, 197, 198, 200 and 201 km/h). However, the dynamometer car tracks the current speed every half second on a paper roll moving 24 in (610 mm) for every mile travelled. Speeds could be calculated by measuring the distance between the timing marks. Immediately after the run staff in the dynamometer car calculated the speed over five second intervals, finding a maximum of 125 mph (201 km/h). Although 126 mph (203 km/h) was seen for a single second, Gresley would not accept this as a reliable measurement and 125 mph (201 km/h) an hour was the figure published.

Gresley planned to have another attempt in September 1939, but this was prevented by the outbreak of World War II. In 1948, plaques proposed and designed by Harry Underwood, a headmaster and keen steam enthusiast, were fixed onto the locomotive which stated 126 mph (203 km/h), and this became the generally accepted speed. Despite this, some writers have commented on the implausibility of the rapid changes in speed. A recent analysis has claimed that the paper roll was not moving at a constant rate, and the peaks and troughs in the speed curve resulting in claims of 125 mph (201 km/h) held for 5 seconds and 126 mph (203 km/h) for one second were just a result of this measuring inaccuracy. It concluded that a verifiable maximum speed being a sustained 124 mph (200 km/h) for almost a mile. On 3 July 2013, the 75th anniversary of the speed record, all six surviving A4 locomotives were brought together at the National Railway Museum.

Rival claims

Mallard's record has never been officially exceeded by a steam locomotive, although a German DRG Class 05 reached 124 mph (200 km/h) in 1936 on a horizontal stretch of track, unlike Stoke Bank, which is slightly downhill. However, the Class 05 hauled a four-coach train of 197 tons, whereas Mallard's seven-coach train weighed 240 tons.

Several speed claims are tied to the Pennsylvania Railroad and their various duplex locomotive classes. The S1 class during its lifetime was attributed to having reached anywhere from 133.4 mph (214.7 km/h) to 141.2 mph (227.2 km/h). Speed claims tied to the T1 class state the locomotive reached speeds up to 140 mph (230 km/h). New build project Pennsylvania Railroad 5550 which is constructing a brand new T1, has stated their desire to test the locomotive when completed to see if it can claim the speed record from Mallard.

{snip}

Mallard at the National Railway Museum, York

Type and origin

Power type: Steam

Designer: Nigel Gresley

Builder: LNER Doncaster Works

Serial number: 1870

Build date: 3 March 1938

Withdrawn: 25 April 1963

Restored: 1963

Disposition: On static display at the National Railway Museum, York

LNER Class A4 4468 Mallard is a 4-6-2 {"Pacific"} steam locomotive built in 1938 for operation on the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) at Doncaster Works to a design of Nigel Gresley. Its streamlined, wind tunnel tested design allowed it to haul long distance express passenger services at high speeds. On 3 July 1938, Mallard broke the world speed record for steam locomotives at 126 mph (203 km/h), which still stands today.

{snip}

1938 speed record

On 3 July 1938, Mallard claimed the world speed record for steam locomotives at 126 mph (203 km/h) during a trial run of a new, quick-acting brake, known as the Westinghouse QSA brake. The speed was achieved during the downward grade of Stoke Bank, south of Grantham at milepost 90¼, between Little Bytham and Essendine stations. Mallard hauled a seven-coach train, including a dynamometer car which housed apparatus to record the speed. The speed it recorded exceeded the previous record speed of 124.5 mph (200.4 km/h) set in Germany in 1936 by DRG Class 05 No. 002. Mallard was just four months old at the time of the record, and was operated by driver Joseph Duddington, a man renowned within the LNER for taking calculated risks, and fireman Thomas Bray. Upon arrival at London King's Cross, driver Duddington and inspector Sid Jenkins were quoted as saying that they thought a speed of 130 mph (209 km/h) would have been possible if the train did not need to slow for a set of junctions at Essendine. There was also a permanent speed restriction of 15 mph (24 km/h) just north of Grantham station, which slowed the train as they sought to build up maximum speed for the descent of Stoke Bank.

The A4 class previously had problems with the big end bearing for the middle cylinder, so the big end was fitted with a "stink bomb" of aniseed oil which would be released if the bearing overheated. After attaining the record speed, the middle big end on Mallard did overheat {and cause the locomotive to be restricted to run at} reduced speed, running at 70–75 mph (113–121 km/h) onwards to Peterborough, and was sent to Doncaster Works for repair. This had been foreseen by the publicity department, who had many pictures taken for the press, in case Mallard did not make it back to Kings Cross. The (Edwardian period) Ivatt Atlantic that replaced Mallard at Peterborough was only just in sight when the head of publicity started handing out the pictures.

Mallard speed record plate

Mallard topped Stoke Bank at 75 mph (121 km/h) and accelerated downhill. The speeds at the end of each 1 mi (1.6 km) from the summit were recorded as: 87.5 mph (140.8 km/h), 96.5 mph (155.3 km/h), 104 mph (167 km/h), 107 mph (172 km/h), 111.5 mph (179.4 km/h), 116 mph (187 km/h) and 119 mph (192 km/h); half-mile (800 m) readings after that gave 120-3/4, 122-1/2, 123, 124-1/4 and finally 125 mph (194, 197, 198, 200 and 201 km/h). However, the dynamometer car tracks the current speed every half second on a paper roll moving 24 in (610 mm) for every mile travelled. Speeds could be calculated by measuring the distance between the timing marks. Immediately after the run staff in the dynamometer car calculated the speed over five second intervals, finding a maximum of 125 mph (201 km/h). Although 126 mph (203 km/h) was seen for a single second, Gresley would not accept this as a reliable measurement and 125 mph (201 km/h) an hour was the figure published.

Gresley planned to have another attempt in September 1939, but this was prevented by the outbreak of World War II. In 1948, plaques proposed and designed by Harry Underwood, a headmaster and keen steam enthusiast, were fixed onto the locomotive which stated 126 mph (203 km/h), and this became the generally accepted speed. Despite this, some writers have commented on the implausibility of the rapid changes in speed. A recent analysis has claimed that the paper roll was not moving at a constant rate, and the peaks and troughs in the speed curve resulting in claims of 125 mph (201 km/h) held for 5 seconds and 126 mph (203 km/h) for one second were just a result of this measuring inaccuracy. It concluded that a verifiable maximum speed being a sustained 124 mph (200 km/h) for almost a mile. On 3 July 2013, the 75th anniversary of the speed record, all six surviving A4 locomotives were brought together at the National Railway Museum.

Rival claims

Mallard's record has never been officially exceeded by a steam locomotive, although a German DRG Class 05 reached 124 mph (200 km/h) in 1936 on a horizontal stretch of track, unlike Stoke Bank, which is slightly downhill. However, the Class 05 hauled a four-coach train of 197 tons, whereas Mallard's seven-coach train weighed 240 tons.

Several speed claims are tied to the Pennsylvania Railroad and their various duplex locomotive classes. The S1 class during its lifetime was attributed to having reached anywhere from 133.4 mph (214.7 km/h) to 141.2 mph (227.2 km/h). Speed claims tied to the T1 class state the locomotive reached speeds up to 140 mph (230 km/h). New build project Pennsylvania Railroad 5550 which is constructing a brand new T1, has stated their desire to test the locomotive when completed to see if it can claim the speed record from Mallard.

{snip}

Pennsylvania Railroad 5550

Wed Jun 19, 2024: On this day, June 19, 1876, British steam locomotive designer Sir Nigel Gresley was born.