Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Virginia

Related: About this forumToday, January 30, is the "Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution" in Virginia.

Sat Jan 30, 2021: On this day, January 30, 1919, Fred Korematsu was born.

Coincidentally, it's Franklin Delano Roosevelt's birthday too.

You owe it to yourself to spend some time reading the Wikipedia article.

Not only should Harriet Tubman be on the $20 it's time to take FDR off the dime and replace him with Fred Korematsu, a welder who challenged the federal government's internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry.

Link to tweet

Fred Korematsu

Born: January 30, 1919; Oakland, California, U.S.

Died: March 30, 2005 (aged 86); Marin County, California, U.S.

Resting place: Mountain View Cemetery; 37°50′06″N 122°14′12″W

Monuments

Fred T. Korematsu Elementary School in Davis

Fred T. Korematsu Campus of San Leandro High School

Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy in Oakland

Fred T. Korematsu Middle School in El Cerrito

Awards: Presidential Medal of Freedom (1998)

Website: korematsuinstitute.org

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu (January 30, 1919 – March 30, 2005) was an American civil rights activist who objected to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of individuals of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast from their homes and their mandatory imprisonment in internment camps, but Korematsu instead challenged the orders and became a fugitive.

The legality of the internment order was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in Korematsu v. United States (1944). However, Korematsu's conviction for evading internment was overturned four decades later in US District Court, after the disclosure of new evidence challenging the necessity of the internment, evidence which had been withheld from the courts by the U.S. government during the war. Eventually, the Korematsu ruling itself was formally condemned seventy-four years later in Trump v. Hawaii, 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

To commemorate his journey as a civil rights activist posthumously, "Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution" was observed for the first time on his 92nd birthday, January 30, 2011, by the state of California, the first such commemoration for an Asian American in the United States. In 2015, Virginia passed legislation to make it the second state to permanently recognize each January 30 as Fred Korematsu Day.

The Fred T. Korematsu Institute was founded in 2009 to carry on Korematsu's legacy as a civil rights advocate by educating and advocating for civil liberties for all communities.

{snip}

Biography

Youth

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was born in Oakland, California, on January 30, 1919, the third of four sons to Japanese parents Kakusaburo Korematsu and Kotsui Aoki, who immigrated to the United States in 1905. Korematsu resided continuously in Oakland from his birth until the time of his arrest. He attended public schools, participated in the Castlemont High School (Oakland, California) tennis and swim teams, and worked in his family's flower nursery in nearby San Leandro, California. He encountered racism in high school when a U.S. Army recruiting officer was handing out recruiting flyers to Korematsu's non-Japanese friends. The officer told Korematsu, "We have orders not to accept you." Even his girlfriend Ida Boitano's Italian parents felt that people of Japanese descent were inferior and unfit to mix with white people.

World War II

When called for military duty under the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, Korematsu was formally rejected by the U.S. Navy due to stomach ulcers, but it is believed that he was actually rejected on the basis of his Japanese descent. Instead, he trained to become a welder in order to contribute his services to the defense effort. First, he worked as a welder at a shipyard. He went in one day to find his timecard missing; his coworkers hastily explained to him that he was Japanese so therefore he was not allowed to work there. He then found a new job, but was fired after a week when his supervisor returned from an extended vacation to find him working there. Because of his Japanese descent, Korematsu lost all employment completely following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

On March 27, 1942, General John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Area, prohibited Japanese Americans from leaving the limits of Military Area No. 1, in preparation for their eventual evacuation to internment camps. Korematsu underwent plastic surgery on his eyelids in an unsuccessful attempt to pass as a Caucasian, changed his name to Clyde Sarah and claimed to be of Spanish and Hawaiian heritage.

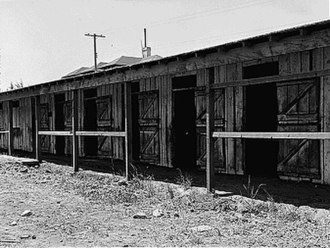

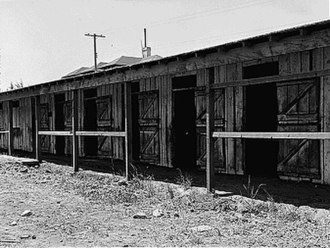

Former horse stalls converted for temporary occupation by Japanese American internees at Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942

When on May 3, 1942, General DeWitt ordered Japanese Americans to report on May 9 to Assembly Centers as a prelude to being removed to the internment camps, Korematsu refused and went into hiding in the Oakland area. He was arrested on a street corner in San Leandro on May 30, 1942, and held at a jail in San Francisco. Shortly after Korematsu's arrest, Ernest Besig, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union in northern California, asked him whether he would be willing to use his case to test the legality of the Japanese American internment. Korematsu agreed, and was assigned civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins. But the national ACLU in fact argued for Besig, its own district director, not to fight Korematsu’s case, since many high-ranking members of the ACLU were close to President Roosevelt and the ACLU didn’t want to be viewed negatively during a time of war. Besig decided to take Korematsu's case despite this.

Korematsu felt that "people should have a fair trial and a chance to defend their loyalty at court in a democratic way, because in this situation, people were placed in imprisonment without any fair trial". On June 12, 1942, Korematsu had his trial date and was given $5,000 bail (equivalent to $78,238.29 in 2019). After Korematsu's arraignment on June 18, 1942, Besig posted bail and he and Korematsu attempted to leave. When met by military police, Besig told Korematsu to go with them. The military police took Korematsu to the Presidio. Korematsu was tried and convicted in federal court on September 8, 1942, for a violation of Public Law No. 503, which criminalized the violations of military orders issued under the authority of Executive Order 9066, and was placed on five years' probation. He was taken from the courtroom and returned to the Tanforan Assembly Center, and thereafter he and his family were placed in the Central Utah War Relocation Center in Topaz, Utah. As an unskilled laborer, he was eligible to receive only $12 per month (equivalent to $187.77 in 2019) for working eight-hour days at the camp. He was placed in a horse stall with a single light bulb, and later said "jail was better than this".

{snip}

Style

{snip}

{snip}

Born: January 30, 1919; Oakland, California, U.S.

Died: March 30, 2005 (aged 86); Marin County, California, U.S.

Resting place: Mountain View Cemetery; 37°50′06″N 122°14′12″W

Monuments

Fred T. Korematsu Elementary School in Davis

Fred T. Korematsu Campus of San Leandro High School

Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy in Oakland

Fred T. Korematsu Middle School in El Cerrito

Awards: Presidential Medal of Freedom (1998)

Website: korematsuinstitute.org

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu (January 30, 1919 – March 30, 2005) was an American civil rights activist who objected to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of individuals of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast from their homes and their mandatory imprisonment in internment camps, but Korematsu instead challenged the orders and became a fugitive.

The legality of the internment order was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in Korematsu v. United States (1944). However, Korematsu's conviction for evading internment was overturned four decades later in US District Court, after the disclosure of new evidence challenging the necessity of the internment, evidence which had been withheld from the courts by the U.S. government during the war. Eventually, the Korematsu ruling itself was formally condemned seventy-four years later in Trump v. Hawaii, 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

To commemorate his journey as a civil rights activist posthumously, "Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution" was observed for the first time on his 92nd birthday, January 30, 2011, by the state of California, the first such commemoration for an Asian American in the United States. In 2015, Virginia passed legislation to make it the second state to permanently recognize each January 30 as Fred Korematsu Day.

The Fred T. Korematsu Institute was founded in 2009 to carry on Korematsu's legacy as a civil rights advocate by educating and advocating for civil liberties for all communities.

{snip}

Biography

Youth

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was born in Oakland, California, on January 30, 1919, the third of four sons to Japanese parents Kakusaburo Korematsu and Kotsui Aoki, who immigrated to the United States in 1905. Korematsu resided continuously in Oakland from his birth until the time of his arrest. He attended public schools, participated in the Castlemont High School (Oakland, California) tennis and swim teams, and worked in his family's flower nursery in nearby San Leandro, California. He encountered racism in high school when a U.S. Army recruiting officer was handing out recruiting flyers to Korematsu's non-Japanese friends. The officer told Korematsu, "We have orders not to accept you." Even his girlfriend Ida Boitano's Italian parents felt that people of Japanese descent were inferior and unfit to mix with white people.

World War II

When called for military duty under the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, Korematsu was formally rejected by the U.S. Navy due to stomach ulcers, but it is believed that he was actually rejected on the basis of his Japanese descent. Instead, he trained to become a welder in order to contribute his services to the defense effort. First, he worked as a welder at a shipyard. He went in one day to find his timecard missing; his coworkers hastily explained to him that he was Japanese so therefore he was not allowed to work there. He then found a new job, but was fired after a week when his supervisor returned from an extended vacation to find him working there. Because of his Japanese descent, Korematsu lost all employment completely following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

On March 27, 1942, General John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Area, prohibited Japanese Americans from leaving the limits of Military Area No. 1, in preparation for their eventual evacuation to internment camps. Korematsu underwent plastic surgery on his eyelids in an unsuccessful attempt to pass as a Caucasian, changed his name to Clyde Sarah and claimed to be of Spanish and Hawaiian heritage.

Former horse stalls converted for temporary occupation by Japanese American internees at Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942

When on May 3, 1942, General DeWitt ordered Japanese Americans to report on May 9 to Assembly Centers as a prelude to being removed to the internment camps, Korematsu refused and went into hiding in the Oakland area. He was arrested on a street corner in San Leandro on May 30, 1942, and held at a jail in San Francisco. Shortly after Korematsu's arrest, Ernest Besig, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union in northern California, asked him whether he would be willing to use his case to test the legality of the Japanese American internment. Korematsu agreed, and was assigned civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins. But the national ACLU in fact argued for Besig, its own district director, not to fight Korematsu’s case, since many high-ranking members of the ACLU were close to President Roosevelt and the ACLU didn’t want to be viewed negatively during a time of war. Besig decided to take Korematsu's case despite this.

Korematsu felt that "people should have a fair trial and a chance to defend their loyalty at court in a democratic way, because in this situation, people were placed in imprisonment without any fair trial". On June 12, 1942, Korematsu had his trial date and was given $5,000 bail (equivalent to $78,238.29 in 2019). After Korematsu's arraignment on June 18, 1942, Besig posted bail and he and Korematsu attempted to leave. When met by military police, Besig told Korematsu to go with them. The military police took Korematsu to the Presidio. Korematsu was tried and convicted in federal court on September 8, 1942, for a violation of Public Law No. 503, which criminalized the violations of military orders issued under the authority of Executive Order 9066, and was placed on five years' probation. He was taken from the courtroom and returned to the Tanforan Assembly Center, and thereafter he and his family were placed in the Central Utah War Relocation Center in Topaz, Utah. As an unskilled laborer, he was eligible to receive only $12 per month (equivalent to $187.77 in 2019) for working eight-hour days at the camp. He was placed in a horse stall with a single light bulb, and later said "jail was better than this".

{snip}

Style

{snip}

• On September 23, 2010, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger of California signed into law a bill that designates January 30 of each year as the Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution, a first for an Asian American in the United States. It was observed for the first time on January 30, 2011. The main celebration of the California state was held at the Wheeler Auditorium on the University of California, Berkeley campus, sponsored by the Korematsu Institute, a non-profit program co-founded by Korematsu's daughter Karen Korematsu to advance racial equity, social justice, and human rights as well as the Asian Law Caucus, a San Francisco-based civil rights organization. The event included presentations by the Rev. Jesse Jackson and a screening of the Emmy Award-winning film Of Civil Wrongs and Rights: The Fred Korematsu Story.

• In 2015, the Commonwealth of Virginia established January 30 as "Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution" beginning in 2016.

{snip}