Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

The DU Lounge

Related: Culture Forums, Support ForumsThe erotic poems of Bilitis

A lush translation of this late-discovered lesbian poet added to the legacy of Sappho, but there was a trickster at work

https://aeon.co/essays/how-a-playful-literary-hoax-illuminates-classical-queerness

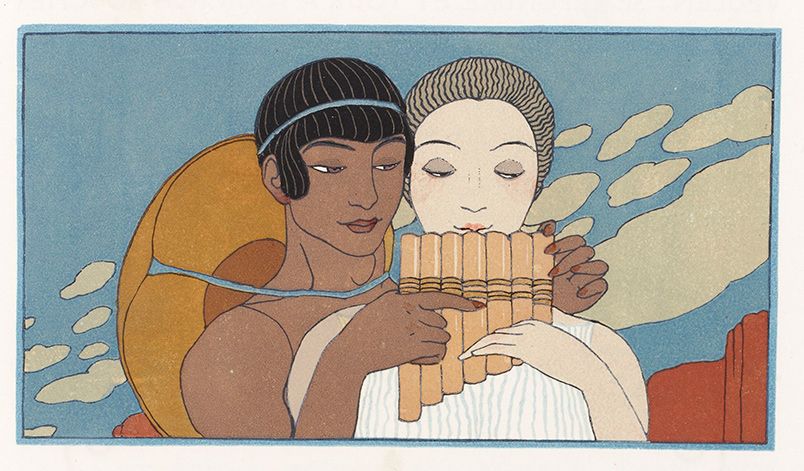

From The Songs of Bilitis (1922) by Pierre Louÿs, illustrated by Georges Barbier. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

In 1894, a German archaeologist named Herr G Heim made a groundbreaking discovery. On the island of Cyprus, he excavated a tomb that belonged to a hitherto unknown ancient female poet by the name of Bilitis. Carved on the walls surrounding her sarcophagus were more than 150 ancient Greek poems in which Bilitis recounted her life, from her childhood in Pamphylia in present-day Turkey to her adventures on the islands of Lesbos and Cyprus, where she would eventually come to rest. Heim diligently copied down this treasure trove of poems, which had not seen the light of day for more than two millennia. They would have remained little known – accessible only to a small, scholarly audience who could decipher ancient Greek – had a Frenchman named Pierre Louÿs not taken it upon himself to hunt down Heim’s Greek edition, hot off the press, and translated Bilitis’s poetry into French for a broader reading public that same year (published as Les Chansons de Bilitis or The Songs of Bilitis). Bilitis might have been an obscure historical figure – no other ancient author mentions encountering her or her poetry – but the cultural and literary significance of Heim’s discovery was not lost on Louÿs. For, in several of her poems, Bilitis revealed that she crossed paths with classical antiquity’s most renowned and controversial female poet: Sappho.

From The Songs of Bilitis (1922) by Pierre Louÿs, illustrated by Georges Barbier. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

Sappho (c630-c570 BCE) lived in the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, where she composed lyric poetry – songs performed to the accompaniment of the lyre. Her poetry was widely admired throughout antiquity. Plato dubbed her ‘the tenth Muse’. In the 1st century CE, the Greek philosopher Plutarch recalled listening to Sappho’s poetry performed at symposia – wine-drinking parties – remarking that her words were so beautiful, he was moved to put his wine cup down while he listened.

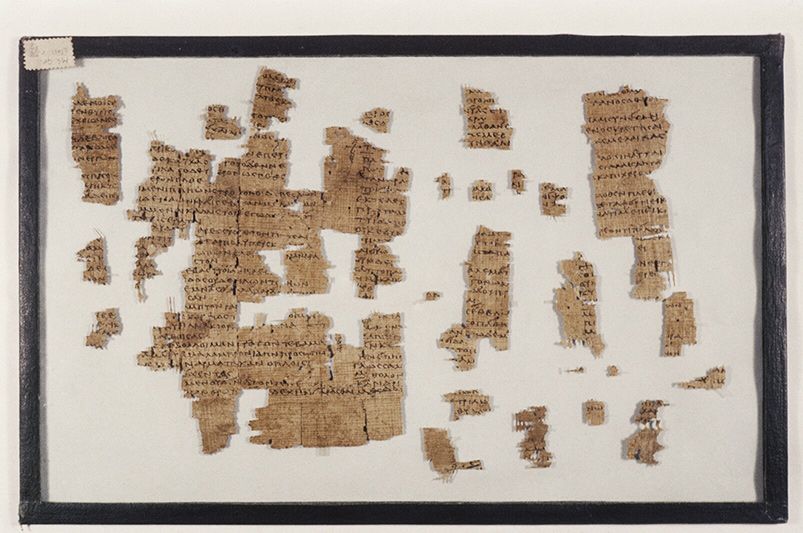

A 3rd-century Egyptian fragment of Sappho’s poetry from papyri found at Oxyrhynchus (modern-day Al-Bahnasa in Egypt). Courtesy the Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK

Sappho was significant enough to have her work copied by scholars at the Library of Alexandria a few hundred years after she lived – the same scholars who first systematised Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey into the books we are familiar with today. Of the nine book rolls of Sappho’s work these scholars produced, only a sliver survives. There is one complete poem, the so-called ‘Hymn to Aphrodite’, in which Sappho prays to the goddess of love to bring a female lover back into her good graces. The rest are scraps. Our knowledge of her poetry relies largely on papyrus fragments and partial quotations from later authors. As the classicist Emily Wilson put it in the London Review of Books: ‘Reconstructing Sappho from what remains is like trying to get a sense of a whole Tyrannosaurus rex from one claw.’ Among these precious fragments, we find some of the most stirring and exceptional representations of desire in all ancient Greek literature. In fragment 31, for example, Sappho sees a man sitting across from a woman and listening to her sweet voice and lovely laugh. She compares him to a god, but then this man, ‘whoever he is’, quickly fades to the background, and Sappho spends the rest of the fragment expressing in hair-raising detail the effects that beholding this woman has on her:

From The Songs of Bilitis (1922) by Pierre Louÿs, illustrated by Georges Barbier. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

Passionate desire, what the Greeks called eros, is no trifling matter for Sappho. In fragment 130, Sappho calls eros the ‘melter of limbs’ who habitually stirs her, a ‘sweetbitter [glukupikron] unmanageable creature who steals in …’ If we are accustomed to think of love as bittersweet, Sappho inverts this: eros starts off sweet (gluku) but turns bitter (pikron), as some distance or barrier often comes between Sappho and her female loves, as in fragment 31 above. We find expressions of the devastating stakes of eros among male lyric poets, too, but in those contexts, the poets sing of desire for beautiful male youths or ‘beloveds’. In classical Greek culture, this form of male homoeroticism, known as pederasty, is elevated as the most admired, virtuous, manly form of love, even superior to heterosexual relations. From our earliest Greek literary sources onwards, women’s desires and bodies are problematic. According to the poet Hesiod, Zeus invented the first woman – Pandora, a ‘beautiful evil thing’ – as a punishment for men. Her opening of the jar – not a box but rather a pithos, a giant storage jug as big as the human body – symbolises the misogynist view of women as leaky containers whose insatiable appetites, whether for food or for sex, must be controlled and regulated by men.

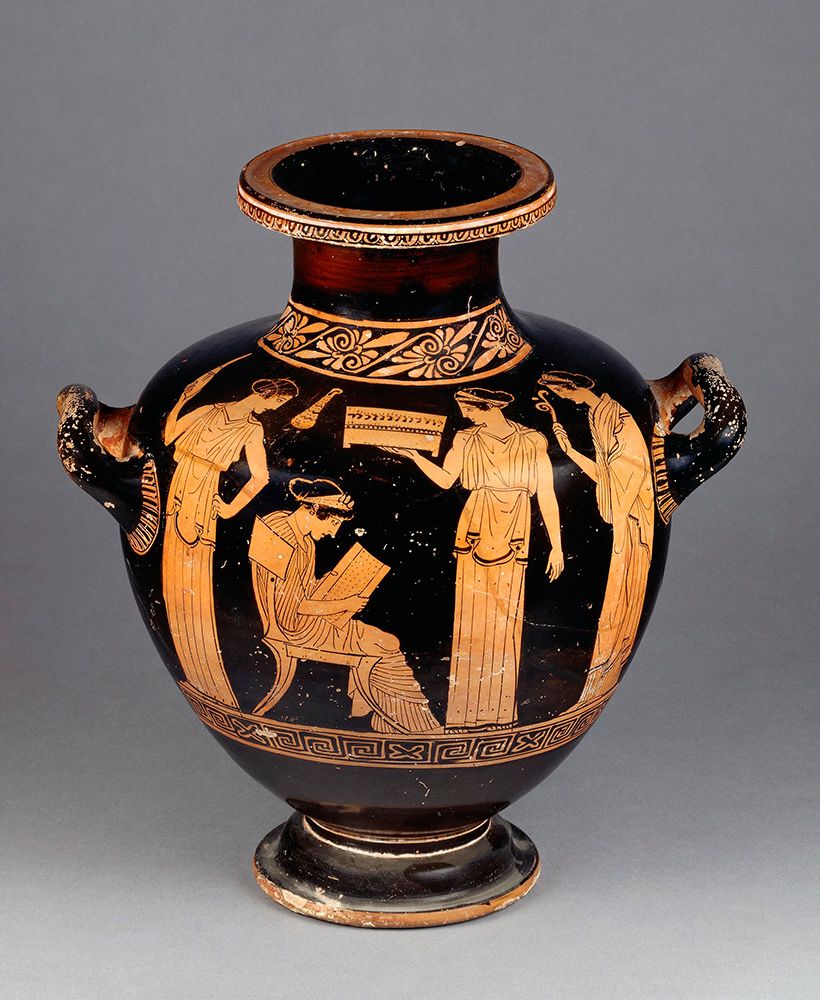

A hydria (water jar) possibly depicting Sappho reading and surrounded by attendants. Greek, c450 BCE. Courtesy the British Museum, London

snip